Clark’s Cost of Attendance Will Increase, Again

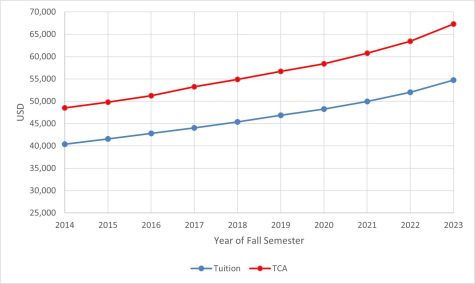

The cost of tuition for the 2023-2024 academic year at Clark University is set to increase by $2,750 to now total $54,760, according to public data available on the undergraduate admissions webpage.

Along with other rising fees, the change in tuition brings the total cost of attendance (TCA) for a first-year undergraduate student – or the “sticker price” – to $67,277. Sticker price is calculated by summing the costs of tuition, standard room and board, and any fees associated with first-time enrollment.

Nationwide, the average cost of tuition and fees at a private college was $39,723 for this academic year, according to a study conducted by U.S. News and World Report in September of 2022.

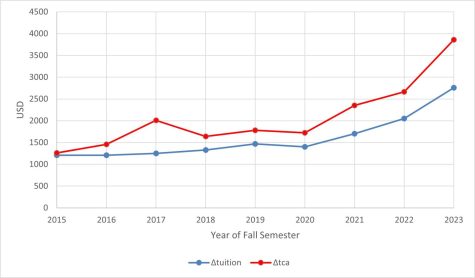

The changes at Clark represent an increase of approximately 5.3 and 6.1 percent for tuition and total cost of attendance, respectively, from the 2022-2023 year.

Abby Wilkes, a sophomore at Clark, said that her immediate reaction to the price increase was, “Crap! How am I going to make these extra thousand dollars in the summer?” Wilkes explained that she was notified of the change by an email sent to the sophomore class on March 20. The email, sent from the Office of the President, encourages concerned students to “please contact the Office of Financial Assistance.” A separate but identical email was sent to the freshman class on the same day. Interviews with upperclassmen suggested that juniors and seniors were not contacted.

The Office of the President did not respond to our request for comment.

“I think it’s messed up,” said Omar Sullivan, a master’s student in the 5th year program. “I feel like some degree of raising tuition is expected, but to raise it that much is a little duplicitous,” he said.

The price of a Clark education has historically risen every year, like at most private universities in the United States. But the change scheduled to begin this fall is one of the most significant one-year price increases in recent history for Clark.

Over the last decade, the change in tuition and cost of attendance year-over-year was relatively consistent at Clark. Tuition increased by approximately $1,250 each year, while sticker price rose by just over $1,500. That changed in 2021 when costs jumped upwards, a trend that has continued into this year and the next.

Students who spoke with The Scarlet are concerned about affordability. Ruth Babich, a sophomore, said that one of the reasons she came to Clark was because of the financial aid she received. “Now they’re increasing the price of tuition, but aid’s not really going up,” she said. Babich, who works as an RA, said that her “residents have been really concerned about the prices going up.”

“They complain about it, but we all have the feeling that there’s nothing we can do about it,” she said.

Aaron Richmond-Crosset, another sophomore, is also worried about the burdens that higher costs bring. “I’m concerned that the aid that Clark gave me did not increase, but the price increased, which is super frustrating,” he said. Richmond-Crosset said that no one from Clark had told him if his financial aid would be raised, and that the Office of Financial Assistance had not contacted him.

The Office of Financial Assistance did not immediately respond to our request for comment after nine days.

The implementation of increasing costs corresponds with two transformational events for the University: the installation of David Fithian as Clark’s 10th President, and the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fithian began his term over the summer of 2020, at the height of the pandemic.

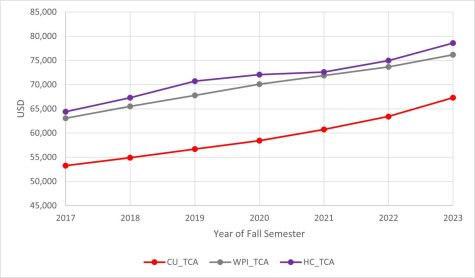

Compared to other schools in the area such as Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) and The College of the Holy Cross, Clark’s total cost of attendance has historically been about $10,000 less expensive. Next fall, a year at Holy Cross will run students nearly $80,000. At WPI, costs total over $75,000.

Espi Garschina-Bobrow, a sophomore, was concerned about the additional debt she may be forced to incur because of Clark’s rising costs. “I have two younger siblings, so my parents don’t pay that much for school, which means I’m paying for it with my future,” she said. “It just feels icky. And I know that when I take out a loan for next year, because I do it every year, it’s going to feel even ickier,” she said.

Ryan Hovey, another member of the class of 2025, seemed to concur. Hovey was concerned about paying his bills to Clark for the coming year, particularly because he draws his funding from a variety of different sources. “Maybe it would be loans, and my parents, and it might also be me,” he explained.

“I am fortunate enough to have my parents cover most of the stuff,” said Jade Newman, a junior. Newman was worried for her friends who don’t have that same luxury – “if they were in this situation, well, they’d be screwed,” she said. Newman suggested that Clark administrators need to improve transparency by explaining why they plan to increase tuition “by that much.”

What We Pay For

At most colleges and universities in the United States, the revenue generated from students is used to pay for year-over-year operating expenditures – the costs that keep the lights on, in short. Clark is no different, according to a December 2022 University Financial Update obtained by The Scarlet from a member of the faculty.

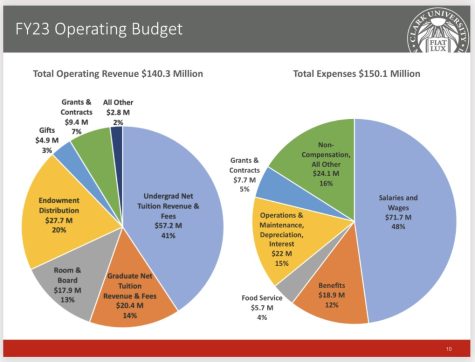

“Clark’s expenditure budget is supported by total revenue received, primarily tuition and fees,” the presentation explains. One slide includes an itemized budget for fiscal year 2023, showing that undergraduate and graduate tuition, fees and room and board accounted for approximately 68 percent of all revenue. In total, Clark received $140.3 million, but stacked up expenses numbering just over $150 million. The university spends most of its yearly revenue – 60 percent – on salaries, wages, and benefits.

Clark’s financial challenge is two-fold. First, according to the presentation, Clark faces the pressure of increasing costs. “The University’s total operating expense increased $20.4 million, or 16 [percent], from FY21 to FY22,” they wrote. The university attributes this partly to inflation, and partly to “returning to normal operations,” from COVID-19. Revenue had also decreased because of “two years of enrollment declines” due to the pandemic, they wrote.

Second: all these challenges mean that the university has endured “two years of operating deficits.”

To make up for that deficit, Clark pulls from its endowment funds. Internal rules dictate that the university is only allowed to collect a certain amount per year – called the “annual distribution rate” – subject to the approval of the Board of Trustees. Historically, this rate was set at 5 percent. It was increased to 6 percent for fiscal year 2023, according to the presentation. This is accounted for in the “revenue” pie chart as “endowment distribution,” representing 20 percent of total revenue.

As the “expenses” pie chart reveals, revenue is not used to fund major capital projects like new buildings. Investments such as the new Center for Media Arts, Computing and Design are funded almost singularly through debt – loans – and by philanthropic gifts to the university.

In his 2022 State of the University address, given on Dec. 20, President David Fithian urged patience as the university realized its “overall financial strategy.” He promised to continue “prudent investing rather than across-the-board belt-tightening” even while facing deficits. “We expect that many of the investments we are making now will increase revenue and strengthen our operating budget in the years ahead,” Fithian said.

He explained that the university is aiming to enter fiscal year 2025 with a balanced budget. And next year, according to the presentation, Clark is budgeting for “an across-the-board base salary increase of 3 [percent.]”

Even with this reassurance, anxiety is still running high among Clark students.

“I think the Clark community has a lot of networks for students to support students, but something like this – it kind of just shoots everyone in the foot,” said Abby Wilkes. “I think it’s not fair. They have pockets they can reach into,” she said.