Stephen DiRado is a film photography professor at Clark, recognized on campus and in his field for his well-known work. DiRado started at Clark 41 years ago, when he was just 23. When asked why he decided to teach for the University, DiRado said, “I didn’t. It kind of called me.”

Professor DiRado discussed his career, the art of photography, and more in an interview with The Scarlet.

DiRado: “So I just finished college and I had a show in a local gallery of photographs. And the person that came to review this show… while interviewing me, this person says, ‘I am the program director for studio at Clark University. You wouldn’t happen to know anybody who would like to come to the university and run the analog photo darkroom complex?’ And I said, ‘I’m your person.’ And I was hired right then and there on the spot. And that was one of the beginnings of my humble career, the fall of 1982.”

Early Life, College

From a young age, DiRado was surrounded by photography and art. His father was an artist who worked as a commercial photographer, collaborating often with others around Massachusetts.

DiRado: “I got to hang out as a kid, 10, 11, 12 years old with these amazing photographers. In an era that was very glorious, they had the big cameras with the flashbulbs, and they just looked cool the way that they walked around… and I was infatuated by that. And so these amazing people… took me under their wing, along with my father, to show me the basics of how to make a photograph, the old analog way of developing film and making prints.”

DiRado’s love for photography continued to grow. In high school he started a photo club. At 14 years old, he was teaching fellow students how to take photos and develop them. While he was doing this, he also was a part-time journalist for an annex to the Worcester Telegram & Gazette called the Marlboro Sun. “On weekends I took on assignments and traveled all around the central Massachusetts area, photographing everything from sports to weddings to political events,” DiRado said.

At college, DiRado was exposed to fine art photography, which was very different from what he already knew. “It was all about me, me, me, and no longer service to others,” DiRado said, comparing it to the work of photojournalism. “It was very personal,” he said.

He always knew he would pursue photography professionally, but never thought he’d be teaching. DiRado didn’t care much for public speaking. Right out of college, though, he was given the opportunity to teach a high school enrichment program. DiRado was worried that the students wouldn’t take him seriously, given his young age. As the first day of classes approached, DiRado said he was scared to death – he couldn’t eat or sleep.

The first class went pretty well. “When I came into the second class thinking I was a big deal,” said DiRado, “I had a panic attack in front of everybody.”

“I remember leaving. ‘Excuse me, class, I have to go get a drink of water, I’ll be back.’ I remember hitting my head against the wall in the hallway next to the water fountain. ‘Go back back there and teach that class! This is where you’re going to end up in the future. This is your destiny. Don’t be a big deal when you’re not a big deal. Be humble because that’s what you are right now. And just fess up that you’re nervous.’”

DiRado went back into the classroom. “Excuse me, class – I’m really nervous,” he told the students. “And they all rubbed my back. They all get up off the chairs [and said], ‘No, you’re doing fine.’”

At that moment, DiRado had an epiphany. “I realized that I’m vulnerable, I’m awkward, but I have something to say. And as a teacher, I had something to offer. I’ve been like that ever since, even to this day, at 66 years old, I’m still very humble… it all started to really formulate right then and there.”

DiRado on his method: “I think of it that way, like if I was to write about this photograph, and if it’s about two people in an environment, have the two people very clearly visible in the photo, probably have them engaged in something in that environment, so there’s a connection there. And have enough in the photo of the environment that they’re in, that they’re involved in. It’s not a complete narrative because we don’t know if they walked into the room or if they’re leaving the room. We don’t know what their actual job is or their connections, but it’s enough there for the subtext of the byline to fill in those spaces”

On preparing for his career: “I realized coming out of college that I was becoming a hybrid, a little bit of both worlds, kind of unique, kind of a very personal journalism as opposed to being of service to a newspaper or magazine, but something that was far more creative and expressive…”

When he left college, he realized he laid the foundation for the rest of his life and this is what he was interested in. “So coming out of college, coming here to teach, I started looking for photo essays, things that I could do exactly that; reach out to a certain community” he said.

Projects: Bell Pond

“Bell Pond was my first leap into [the fine arts] world,” DiRado said. Bell Pond was his first large project out of college. This collection was shot in 1983 at Bell Pond in Worcester.

The project began when he came across a park with a pond in the summertime which was filled with community members enjoying the water and environment. DiRado decided that this park, Bell Pond, would become his next project.

“[I would] introduce myself with these funny box cameras with a bellows, analog film plates of films that go on them. I would ask permission if I could stay with them for the rest of the summer and they miraculously said yes. And so every single day after my regular jobs, not teaching during the summer – literally washing windows, that’s how I was making a living. And then after work at 3 p.m., I’d go to Bell Pond.”

“And I would photograph people day after day after day, and I would give them the photos the following day. I would print them that night. I would make notes of the things that I was doing and the next day I would hand them [their photograph]. ‘Wow, that’s me. That’s really cool. And so what do you think about it?’”

“So I would have this conversation. ‘Whenever you are ready? We should make another one. But why don’t we make it so it’s collaborative?. So it’s something the two of us feel about this.’ So I was learning on the spot, learning on location, about this kind of what they call social sculpture, where it’s something where I’m interacting with my community that I’m integrating, assimilating into that community.”

Over the course of the summer, DiRado made more relationships with the community, his subjects. DiRado said he still meets for coffee with people he photographed in 1983. Many of them still have the prints DiRado gave them, he said.

“It just blew my mind back then and now it’s very emotional to see that these people still think of me in a very fond way. I’ve had people on the street pull up or pull the car off and give me a big hug and just thanked me for that wonderful time back in ‘83. That’s part of the art. I want to make that clear that that kind of connection. That kind of interaction is as much about the photo as the whole process being about the art as well.”

Soon, Davis Publishing, here in Worcester, will be publishing a book of Stephen DiRado’s Bell Pond.

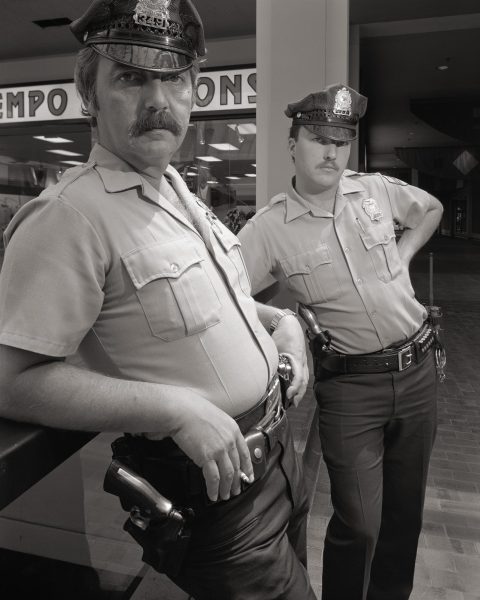

Projects: Mall

From Bell Pond, DiRado continued to another series called ‘Mall.’ He hung out in a mall in Worcester called The Galleria for two and a half years.

“By dumb luck, I happened to be there at the right time to capture its absolute brilliance but also its downfall where the whole world was shifting from large malls to smaller strip malls or whatever or more defined stores,” he said.

DiRado caught a very important time in the history of malls. When he was just 27 years old, the pieces from this series became a show at the Worcester Art Museum. The project was recently featured again in an article by Margaret Talbot in The New Yorker.

Projects: With Dad

“With Dad” came out as a book three years ago. The project focuses on DiRado’s father, who succumbed to Alzheimer’s over a 20-year period. DiRado’s father was a photographer, painter and illustrator.

DiRado’s father told him at a young age that there’s no business or money in photography. But DiRado’s family is used to him having a camera, always documenting their lives.

When DiRado was in his late 30’s, he approached his father about photographing him. “For the next couple of years at the beginning, once every two months… I’d go to my parents’ house, take my father – ‘let’s go outside. Let me take some photos of you,’” DiRado said.

The series shows every part of his father’s life; family, holidays and paintings. DiRado continued to take photos as his father’s condition advanced. “Why am I photographing him? I had no choice, I had to,” he said.

“I had to hold onto him and love him. Love him with my camera and respect him. It’s the way I know best, it gave me the responsibility of a job,” said DiRado.

As his dad became more ill, DiRado continued to visit his dad more. Photographing his father in a nursing home was DiRado’s favorite project, he said. “I learned so much there, more than any other place in my life.” The overall project captured the love that DiRado has for his father.

Conclusion

Many of DiRado’s works have received popular acclaim. But for DiRado, there are many that he finds special that have not been recognized the way other pieces have. “I’m never fully happy [with my projects]. I always feel they’re not completely resolved and there’s a part of me that thinks that if that happens, then I’m dead as an artist that is no more growth.”

DiRado chooses a series to work on, and will keep working until he reaches a dead end in the creative process. “I’m very disheartened by it. Defeated by it. Depressed by the fact that I can’t resolve it. And I know intellectually that what’s happening is growth. I never ever completely abandoned something – it goes through a metamorphosis and becomes something else. It just doesn’t come off easy though, there’s nothing easy about that transition, it is very painful,” he said.

In his home he has more than 30,000 photos that he has shot and developed over his lifetime. He has not counted them all because he is always working, recording and printing. He doesn’t want them removed from his house and archived because “they’re all my babies and I just don’t want to have an empty house,” he said. “They’re all of my heart and soul and spirit that I surround myself with. And every day I go into these rooms, plural, with all of these photos and frames and boxes and they’re proof that I’m achieving something in my lifetime.”

“That I’m doing something that I hope is of value to others and for future artists, admirers, historians, to study that showed that I did live on this earth, however brief that time is. I don’t care if I live to be 102.”